Portfolio

Lion’s Head – Portland 2024

This project features a hand-carved lion’s head water spout, crafted from a solid block of Portland stone over three months. 🦁💧 I took on this piece as a personal challenge to create something bold and enduring, and it will soon become the centrepiece of a custom water feature in my garden.

The carving process involved everything from rough outlining to the fine details that bring out the lion’s unique expression. In the time-lapse video below, you can watch as the lion’s face gradually takes shape, transforming from raw stone into a characterful sculpture ready to spout water and add depth to my outdoor space.

The Jaws of Time – Marble 2021 (SOLD)

The Jaws of time is a marble piece that took me several years of work to complete. The marble was a recycled elongated block (most probably an architectural component) and old, meaning that it was extremely tough to carve with hand tools. On top of this the inclusion of the scorpion (a real scorpion!) into the resin had some issues as you can see from the appearance of a trapped gas bubble on top of its head. The idea was to represent the Gates of the Afterlife beyond which Eternal Death awaits, hence a deadly scorpion. I made a cool video using Heavy Metal music that I think it complements perfectly with the piece. Enjoy.

Deliverance – Portland – 2020

First attempt at sculpting something other than heads and anatomical pieces. I quite enjoyed it and I feel like this could become a lovely art decor piece for any home.

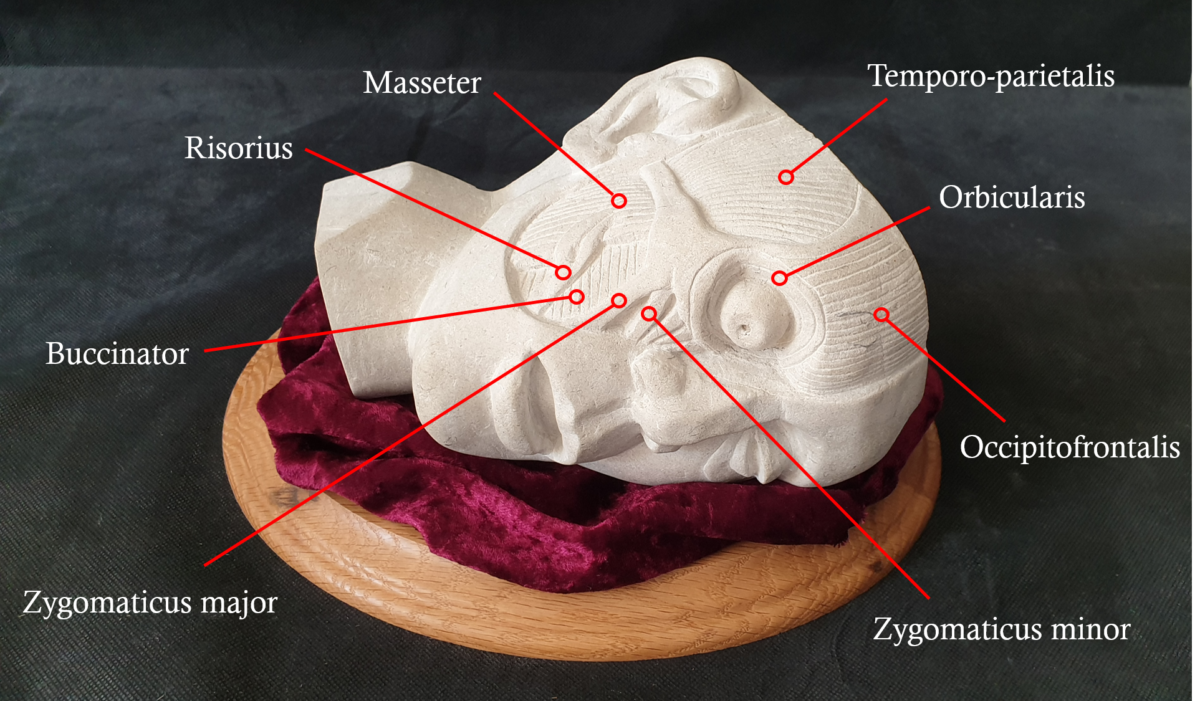

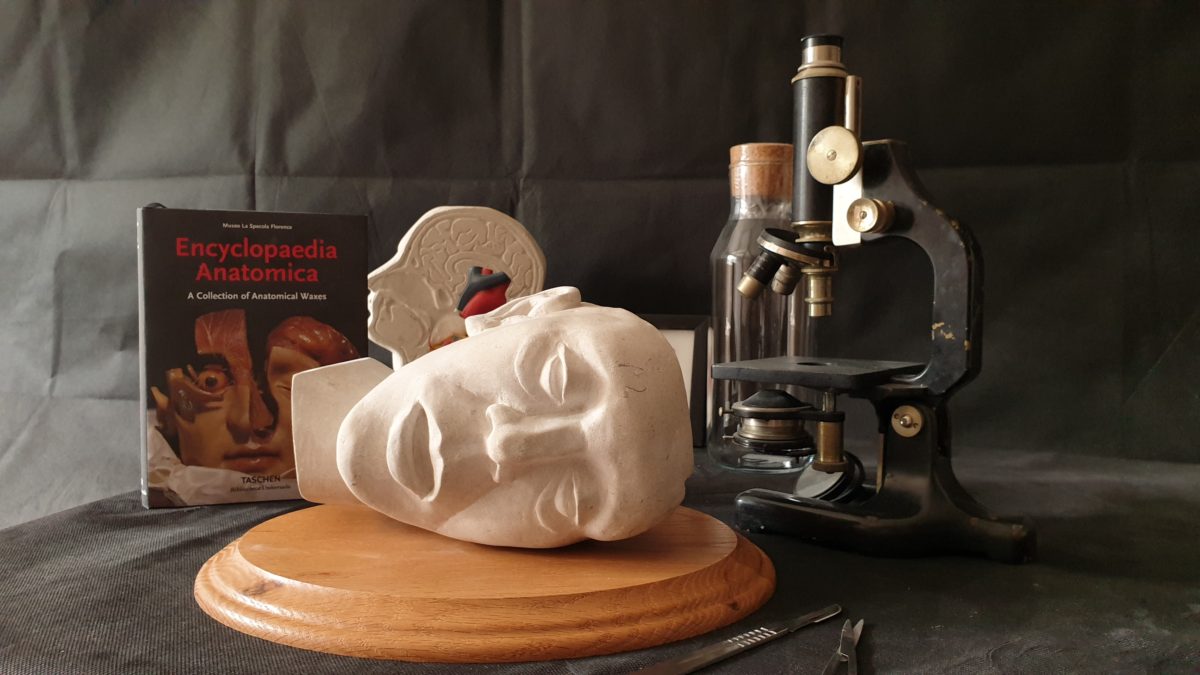

Anatomical dissection of Herbert West -2019

I’ve been lucky enough to be able to practise my dissection skills on a real human head. Here you can see the video before and after dissection.

Just kidding. The “dissected head” was just carved in stone, in Portland stone to be more precise. I went through the trouble of carving a complete head of a deceased man, only to then carve half of his head out. I could have simply carved the right side of his face only and save me the trouble but I wanted this to look and feel like a proper dissection.

But that was not the main challenge of this piece. For years I’ve studied how to make a face look as much alive as I could and I had to forget all of that and relearn how to carve a dead man. A cadaver is not as easy to carve as you think it is. You have to forget about how a familiar face would look like in your stone. The expression, the muscles, the eyes are incredibly difficult to portrait, let alone carved in a stone.

Some of you have probably noticed that Herbert West comes across as a familiar name (along side other references such as Arkham and the Miskatonic river). It comes from the short novel Herbert West the reanimator from Lovecraft. It was a small tribute to the great author of the cosmic horror. I’ve also put a reference to the preservation technique known as petrification. This practice was very common in the nineteenth century and allowed the soft tissues of a corpse to be preserved for decades. One of the masters of this technique was Efisio Marini. Google his name and you will find a lot of his experiments still preserved to this day. Vanitas

Split – Portland stone – 2019

In 2019 I made this sagittal section of a human head in Portland stone in the tradition of last century’s wax anatomical models.

Vanitas-Portland-2019

This is a section of a human skull carved in Portland stone with a real Common Jay (Graphium doson) butterfly embedded in resin. A vanitas is a symbolic work of art showing the transience of life and the certainty of death very common in the 15th century. It usually depicted a head with half face being a skull, symbolising how life is just a transient phase. I wanted to give the same message merging life and death in the same piece. Thanks to the epoxy resin the butterfly will be frozen in time and “kept alive” for an indefinite time (although not as long as the stone!).

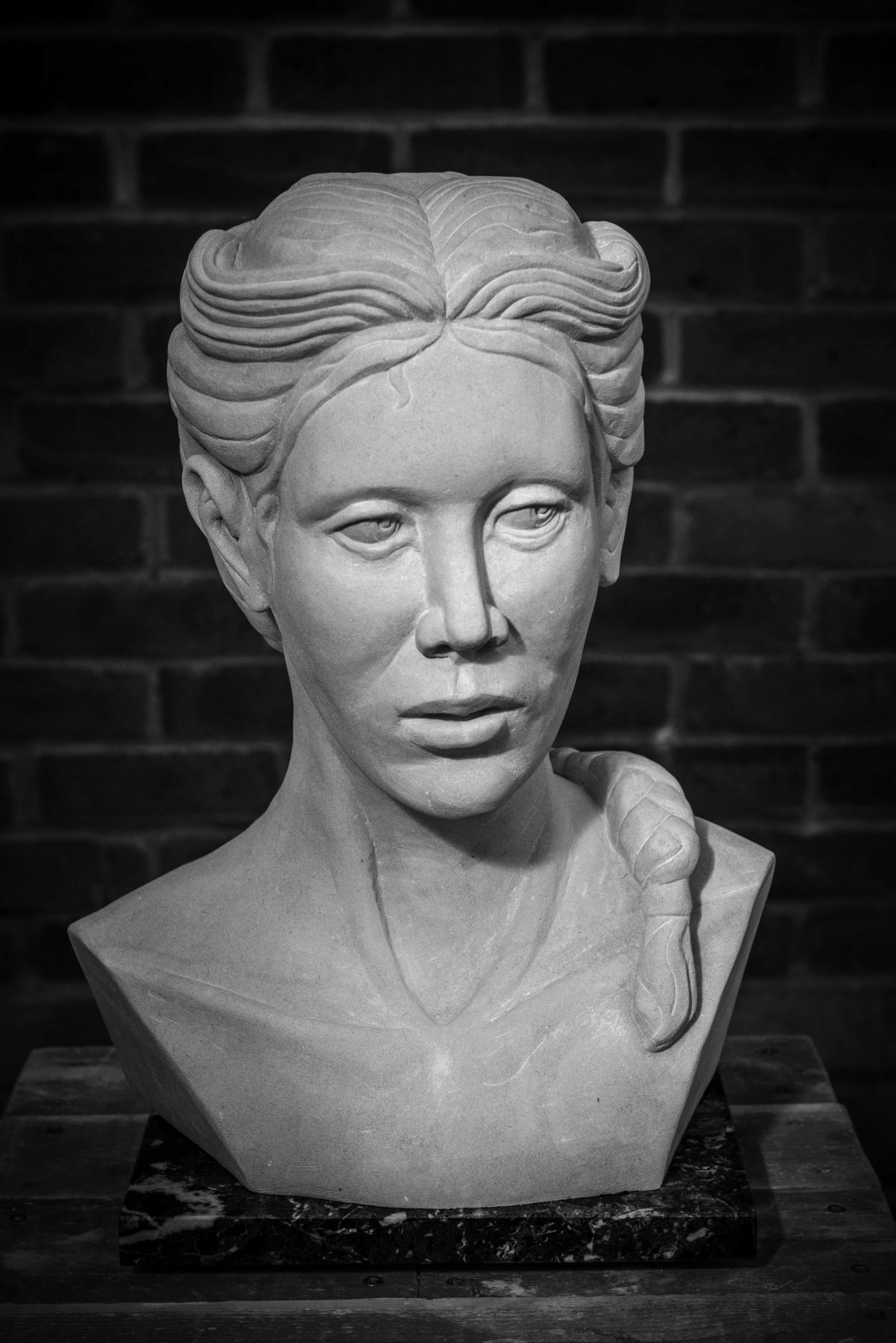

The Three-eyed lady- Richemont blanc- 2019

Is she pretty, isn’t she? But she hides a secret. A third eye on her back. Is she a monster or a fair lady? A Mrs Hyde in disguise, perhaps?

Not many people see the third eye at first, they have to follow the braid from the shoulder up to to the head and then they see it. I love to see their reactions. Something unexpected, something unusual and then they realise “Ah, hence the name!”.

Sculpted on Richemont Blanc and mounted on a black marble base.

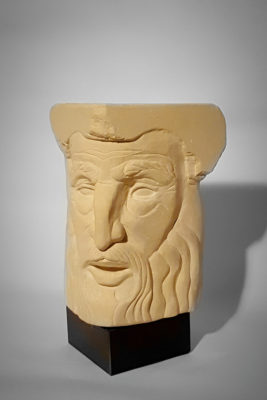

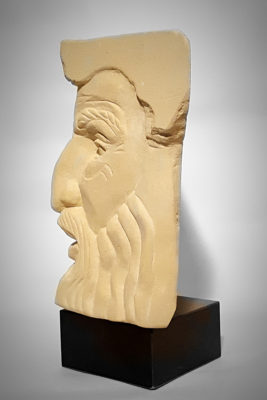

The False Prophet – Richemont Blanc 2018.

The False Prophet, although a minor piece, has been quite important for me. For the first time I carved a face without any model, either clay or photos, or any initial drawing on paper. I simply took the stone and my chisel and worked my way through. It felt liberating because my hands and my mind were free to express themselves without constraints. And it took me just few days to finish it. It has been carved on Richemont Blanc and fixed on a black marble base.

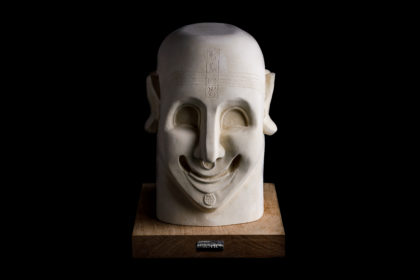

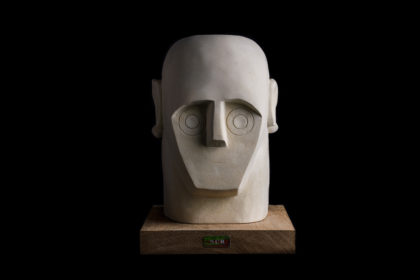

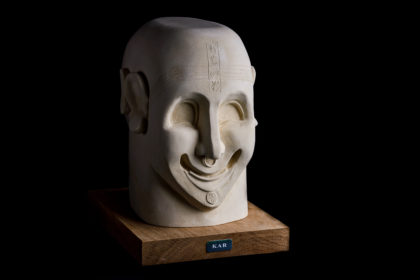

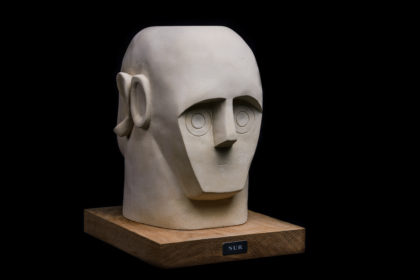

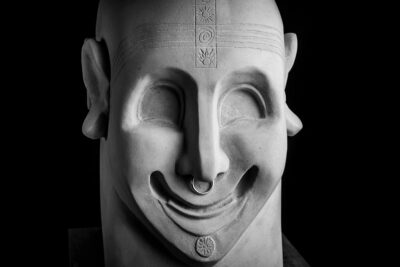

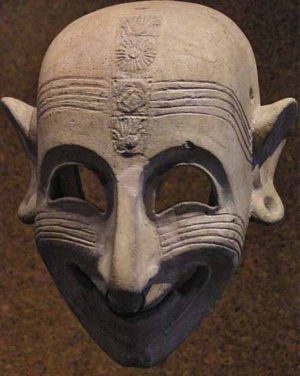

Janus Sardus – maltese stone 2017 (SOLD)

Note/Nota: this page is written both in English and in Italian/questa pagina è scritta sia in inglese che in italiano.

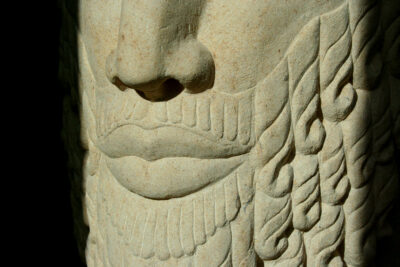

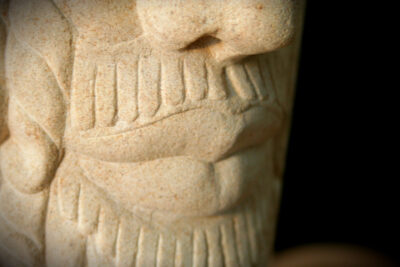

Janus Sardus is a commission from a friend, who is passionate about sardinian history, for a sculpture that could represent Sardinia and/or Cagliari. Janus Sardus takes inspiration from a head of a Gigante di Mont’e Prama from the nuragic period and from a phoenician funeral mask in the hope that it could represent the ancient sardinian identity as a whole, with its duality between native nuragic world and phoenician-carthaginian world. After almost 3000 years and a much more recent troubled history of archeological excavations, the Giants of Mont’e Prama have come to light in all their glory and their linear and geometric heads gave inspiration for the nuragic part of the sculpture. Whereas the typical

Janus Sardus is a commission from a friend, who is passionate about sardinian history, for a sculpture that could represent Sardinia and/or Cagliari. Janus Sardus takes inspiration from a head of a Gigante di Mont’e Prama from the nuragic period and from a phoenician funeral mask in the hope that it could represent the ancient sardinian identity as a whole, with its duality between native nuragic world and phoenician-carthaginian world. After almost 3000 years and a much more recent troubled history of archeological excavations, the Giants of Mont’e Prama have come to light in all their glory and their linear and geometric heads gave inspiration for the nuragic part of the sculpture. Whereas the typical  phoenician-punic funeral masks that have been found around the Mediterranean Sea gave inspiration for the phoenician part. The originals were in terracotta and the adaptation in stone has been particularly difficult so to best convey the typical features of the concavity of a mask. For some the saying “sardonic smile” comes from these sneering masks indeed, almost all found in Sardinia.

phoenician-punic funeral masks that have been found around the Mediterranean Sea gave inspiration for the phoenician part. The originals were in terracotta and the adaptation in stone has been particularly difficult so to best convey the typical features of the concavity of a mask. For some the saying “sardonic smile” comes from these sneering masks indeed, almost all found in Sardinia.

Janus Sardus literally means Sardinian Janus, the two-faced roman god of the beginnings and ends, protector of doors and passages, metaphore of transitions and of the duality of all things. What a better protective deity for this project!

***

Janus Sardus nasce dalla richiesta di un committente, amico e appassionato della storia della Sardegna, di un soggetto che potesse rappresentare la Sardegna e/o Cagliari. Janus Sardus prende ispirazione da una testa di un Gigante di Mont’e Prama del periodo nuragico e da una maschera funeraria fenicia nella speranza che possa rappresentare l’identità sarda antica appieno, con la sua dualità tra mondo autoctono nuragico e mondo fenicio-cartaginese.

Dopo quasi 3000 anni e una più recente travagliata storia di scavi i Giganti di Mont’e Prama sono tornati alla luce in tutto il loro splendore e le teste lineari e geometriche sono state lo spunto per la parte nuragica della scultura. Mentre le tipiche maschere funerarie fenicio-puniche trovate intorno al Mediterraneo sono state lo spunto per la parte fenicia. Le originali erano in terracotta e la trasposizione in pietra è stata particolarmente difficile per rendere al meglio le caratteristiche tipiche della concavità della maschera. Per alcuni l’espressione “sorriso sardonico” deriva proprio da queste maschere ghignanti, quasi tutte trovate in Sardegna.

Janus Sardus significa letteralmente Giano Sardo, il dio romano bifronte degli inizi e delle fini, protettore delle porte e dei passaggi, metafora delle transizioni e della dualità delle cose. Quale migliore nume tutelare per questo progetto!

Our Lady’s Tumbler – Exeter Cathedral’s replica – 2016

The story of this piece goes back to August 2015 when I was asked to make a replica of a medieval corbel from the Exeter Cathedral. The idea was to make it as similar as possible not only in the carving but also in the painting, restoring it the way it would have looked to those that saw it in the 14th century, without damage and in lavish brilliant colours. The 14th century corbel is called Our Lady’s tumbler as it is made of a tumbler and a minstrel that are facing and symbolically entertaining a Virgin Mary’s corbel on the other side of the Cathedral. This originates from a medieval legend quite famous at the time.

The story of this piece goes back to August 2015 when I was asked to make a replica of a medieval corbel from the Exeter Cathedral. The idea was to make it as similar as possible not only in the carving but also in the painting, restoring it the way it would have looked to those that saw it in the 14th century, without damage and in lavish brilliant colours. The 14th century corbel is called Our Lady’s tumbler as it is made of a tumbler and a minstrel that are facing and symbolically entertaining a Virgin Mary’s corbel on the other side of the Cathedral. This originates from a medieval legend quite famous at the time.

In April last year the person that commissioned it, the future painter and I went to Exeter Cathedral, climbed up a scaffolding built for this purpose and took photos and measurements. We couldn’t find any supplier of the original type of stone, Beer Stone, as the quarry has now been shut down but on the recommendations of the cathedral dean we used an equivalent called Richemont Blanc. We bought two blocks from Chichester Stoneworks and I started to carve the tumbler first, then the minstrel. It was extremely difficult at first to get the measurements right. I was working from two-dimensional photos from different angles and I was applying it to a three-dimensional squared stone block. It’s a miracle that I managed to get proportions more or less right! Moreover, the stone was very soft and fragile and a couple of times I managed to knock down a chin or a leaf, luckily all easily amendable. The joined sculpture measures around 1.20 m x 0.50 m together. Later this year it will be painted by the professional conservator Eddie Sinclair using original medieval pigments so to recreate the same colours as it was in the 14th century. And that’s the reason why it has not been sanded down with fine tools, as you can see from the photos. It has a rough look, not refined as it will be covered with gesso for priming and then painted over.

When finished we are also hoping to see it displayed at the Exeter Cathedral itself but I’ll keep you posted about this for sure!

Photos by Marco Brockmann

UPDATE: the painting of the corbel is now finished and you can see the final results here.

Cuaddu – white marble 2016.

I’ve always been fascinated by human features, hence my stress on human faces in my works, but I’ve never realised how beautiful the horse head’s features are. I carved this piece after some weeks of intense studying of horse anatomy. I bought a veterinary anatomy book, I studied skull proportions and muscles position and this is what I got after this journey. Turns out that you just need to move a couple of muscles to change horse’s expression completely. It is true with human faces too, but horses have only 3-4 main expressions, so it’s kind of easier to remodel the head with just few changes. During my carving this horse changed from scared to angry, from relaxed to “ready to action”, like I would describe the final expression I gave to it.

The head is mounted on a black marble base to give maximum contrast with the white.

Regarding the name: cuaddu is the sardinian word for horse (comes from the latin equus) and horses have been highly regarded in Sardinia for centuries.

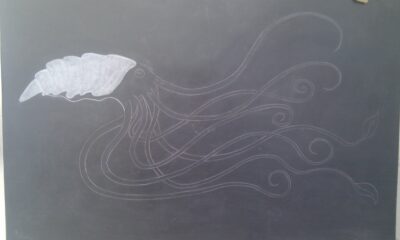

The Kraken – welsh slate 2015

This experimental piece came to my mind one day when I was admiring one of my teacher’s headstones. She was using oil to impregnate a welsh slate so that her letter carving would stand out on a black background. I thought a simple design like a giant squid would look quite nice on a black background. So I tried and here is the result. The carved grey lines of the squid seem almost fluorescent with the black background, which is quite appropriate for a creature of the abyss. The original idea was to have it hanging on the wall with a frame. So one day I was talking with a friend of mine from Bristol that does wealding as a hobby and I came up with the idea of a steel frame. I went to Bristol for a weekend and we had an intensive couple of days in his garage cutting, milling, wealding, grinding and polishing the frame. You can’t believe how much work was behind it. In the end we made it and now the structure should be able to withstand around 20 kilos of stone or more.

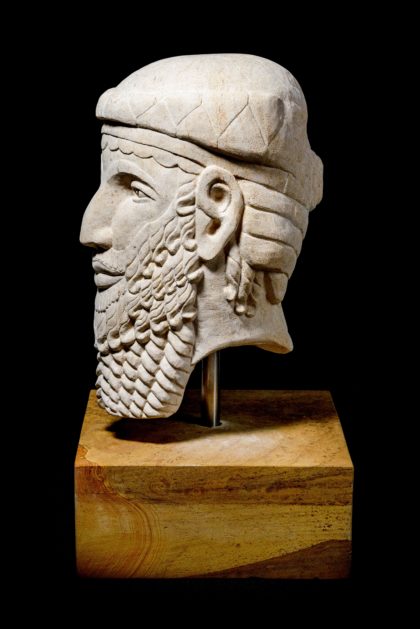

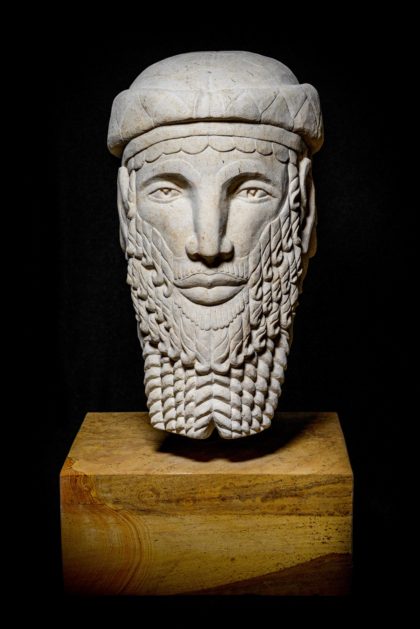

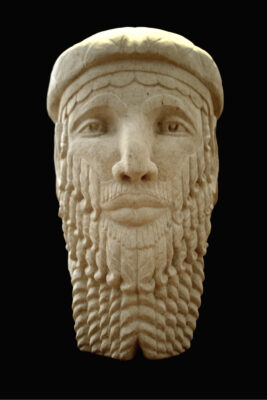

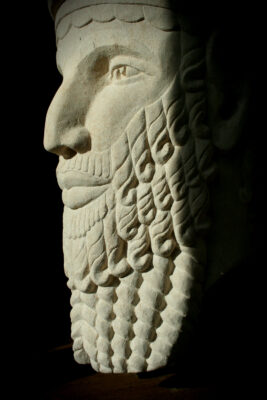

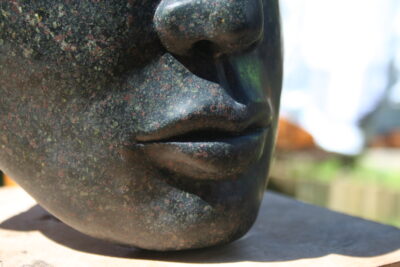

Gilgamesh – Ancaster 2015 (SOLD)

I was looking for a new idea for a head and I came across an assyrian bronze head from Nineveh that caught my attention. It is supposed to be from king Sargon the Great but many think it represents Gilgamesh, the epic hero of the Mesopotamic civilizations. It is incredibly complex in its simplicity of lines and proportions. It carries royalty, strenght and elegance at the same time. Unfortunately the eyes and the ears have been damaged. Usually ancient statues had precious stones instead of eyes and a quick look at contemporary statues suggested me that this head might have had precious earrings too. As new masters conquered Nineveh they gouged these stones out of statues, hence the empy sockets.

The design of the beard is particularly intricate. I loved the beard so I couldn’t resist to carve it. I chose ancaster as it reminds me of a stone that ancient peoples would have used (like egyptians or assyrians -or think about the roman city of Petra in Jordan) and I took some liberties in changing few features like eyebrows’ shape and the bottom part of the beard. Plus I had to “re-invent” eyes, ears and the back of the head since the first two were damaged and the last one wasn’t possible to see due to lack of photos. So it’s a modern take on an ancient classic, although it was never meant to be a copy anyway but just an inspiration for a bearded head. Carving it and studying the perfect proportions of it taught me a lot about the ancient way of highlighting a detail and I am sure I will use these techniques in the future.

Bibliography: Gilgamesh, Stephen Mitchell, Profile books

At peace – Blue lias 2014 (NOT AVAILABLE)

I worked on this piece for almost a month rushing as mad until the last day. The reason was this head was for a wedding gift for one of my dearest friends back in Italy. Inspiration came to me one night when I thought I needed a head that represented something peaceful and quite. A maiden’s face while asleep surrounded by an angel wing. This was carved on blue lias, a soapy stone from South Western England. This represents also my first attempt at carving a feminine face, much more challenging than masculine ones.

Prometheus – Polyphant 2014 (SOLD)

This was my first attempt at carving a human face. Such a challenge but such a satisfaction to have it finished! To carve a face is like to go to the carving gym: you learn so much and you exercise your brain at seriously challenging 3D mind reconstruction. I didn’t have a particular model in mind for this one but I definitely took inspiration from greek and roman pieces. A nose here, an eye there, the lips from a museum, the hair from another. What came out was a collage of different periods and styles. I named it after Prometheus. Prometheus in greek mythology was a titan that stole the secret of fire from the gods and give it to the humans. The first heretic, the first antiestablishment anarchist, the first hero.

I carved it on polyphant, an incredibly versatile type of stone found only in UK. This when carved comes naturally with a light grey colour but when wet it becomes shiny black. So I played with this bichromatic quality of the stone and oiled the face but not the hair. To do so you need to “cook” the stone with hot water to let all the pores open up, then you apply the oil that penetrates the stone and when cold get stuck in. See below the various phases of “cooking” and oiling. The final job is mounted on an oak base.

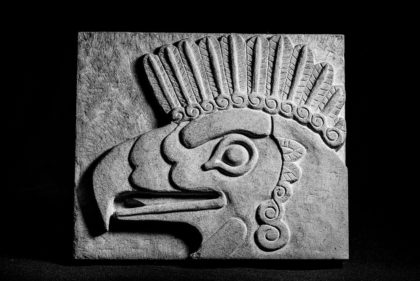

Nimrud – Ancaster 2013

Mesopotamian civilizations, what a wonderful part of history that too often is left aside in our education system. Sumerians, Assirians, Babylonians, Persians are the foundation of our civilization and we dismiss them as minor protagonists of History. Every time I step in the British Museum I remain mesmerised at the beauty of the Assirian collection. The lamassu, half-man and half-bull, are  colossal statues of such a beauty that my heart pounds. And all around them the magnificent bass relieves carved in enormous slabs. The slabs were part of the Nimrud palace and describe the mythology and the every day life of this civilization with incredible detail. These are dated 865 BCE, almost 3000 years ago. 3000 years ago an artist was commissioned by his king to draw these beatiful relieves. And I thought I could homage his craftsman skills by reproducing some of his work. And so this bass relief came to life: it’s an eagle-headed protective spirit and I took some liberties in changing few details here and there. While I was carving it I felt a deep connection with the unknown artist that carved the original 3000 years before me. I had its photos, internet searches so I could document myself further and 3000 years of human kind experience before me. He had only another civilization before his (the sumerians) and basic tools. And nevertheless his job is much better than mine. I called it Nimrud after the city where it was discovered, since it appears these eagle-headed spirits don’t have a name we know of (or yet).

colossal statues of such a beauty that my heart pounds. And all around them the magnificent bass relieves carved in enormous slabs. The slabs were part of the Nimrud palace and describe the mythology and the every day life of this civilization with incredible detail. These are dated 865 BCE, almost 3000 years ago. 3000 years ago an artist was commissioned by his king to draw these beatiful relieves. And I thought I could homage his craftsman skills by reproducing some of his work. And so this bass relief came to life: it’s an eagle-headed protective spirit and I took some liberties in changing few details here and there. While I was carving it I felt a deep connection with the unknown artist that carved the original 3000 years before me. I had its photos, internet searches so I could document myself further and 3000 years of human kind experience before me. He had only another civilization before his (the sumerians) and basic tools. And nevertheless his job is much better than mine. I called it Nimrud after the city where it was discovered, since it appears these eagle-headed spirits don’t have a name we know of (or yet).

Bibliography: Assyrian Sculpture, Julian Reade, The British Museum Press